2019

Time To Transplant Houseplants?

As the end of the growing season approaches, we need to prioritize all the chores that need attention. Do the houseplants require transplanting? The plants that summered outdoors must come back inside soon, before frost damages the foliage or kills the plants.

They’ve been luxuriating on the porch, in higher humidity and brighter light than they usually receive inside. It’s no wonder they look fabulous! So, reintroduce them to indoor conditions while the days are still somewhat long and before the furnace kicks on and dries the air.

Perennials that looked picture perfect in May now look a little stressed after those record high temperatures. And the tired vegetable garden needs fresh compost or aged manure before setting the fall crops.

In a few weeks, flowering bulbs will arrive at garden centers…with pansies, violas, snapdragons, dusty miller, and Heuchera, trailing ivy, and hardy grasses. You’ve been dreaming of those beautiful combination planters, like the ones you saw last autumn at the garden center. But first things first.

Should We Transplant Houseplants Now?

Let’s start with the houseplants. Exposing tropicals to cooling temperatures outdoors, as autumn takes hold, could stress your houseplants. And some of those plants are pleading for attention right now.

While certain plants can tolerate cooler temperatures (cyclamen, ferns, English ivy, succulents, ponytail palm), others can’t. The aroids (peace lily, Dieffenbachia, Anthurium, Philodendron, Alocasia, Chinese evergreen, pothos), prayer plants (Calathea, Maranta), and some of the begonias, for example, should come indoors before temperatures dip below 60°F.

Although they won’t be killed by a few nights in the 50’s, or even the 40’s, you don’t want to prolong their discomfort. Chilling stresses many of our tropical houseplants, and can rot roots and disfigure foliage.

Inspect Them First

Scale on Ficus neriifolia (leaves are 7/16″ wide).

You probably won’t need to transplant houseplants, summering on the porch, that were repotted in the spring. All you need to do now is to inspect them for insects and spider mites before bringing them indoors. Check the bottom of the pot for slugs and sowbugs hiding around the drainage hole.

Clean up the leaves, too, and remove any that are discolored, insect-eaten, or damaged. Peel away the entire leaf, so none of the leaf stems (petioles) remain that later will turn yellow or brown.

After the inspection, clean the pots, wash the saucers, and place the plants in front of the windows where they seemed to thrive last winter.

Horticultural Oil

The dwarf Ficus neriifolia contracted a scale infestation, so I sprayed it with a horticultural oil solution. For insects and mites, horticultural oil works very well. It smothers the pests and is safe to use on most plants, including edibles.

Wiping the horticultural oil solution on smooth leaves (fiddle-leaf fig, pothos, peace lily) with a soft sponge removes dust, grime, and residue from water and fertilizers. It gives them a nice luster without appearing artificial. Read the label; I prefer to use less oil than is recommended on the label—to start with, anyway. Horticultural oil makes surfaces slippery, so be careful.

Do Your Houseplants Actually Need Bigger Pots?

Evergreen bonsai.

Knowing if the plant needs repotting, when to repot, and how large a pot to use is half the battle.

Does it wilt often? Perhaps instead of repotting, the plant needs to be deeply watered. Or maybe the roots have rotted in waterlogged soil, or the water rushes right through without moistening the soil.

I’ve seen a lot of dead plants over the years, and many simply were in pots that were too large. “Aren’t we supposed to transplant houseplants every year, just like our children outgrow their shoes every year?” No; once they have matured, plants can stay potbound for quite some time.

“If I transplant houseplants into bigger pots, won’t that make them grow faster and bigger?” No, another myth! If you transplant houseplants into pots twice the size they need, they more likely will die faster.

Large pots hold large quantities of soil and water. When the moisture is not used by the plant, the sodden mass just sits there, cutting off the oxygen supply and rotting the roots. So, if the entire volume is not tightly filled with roots, the plant doesn’t need to be repotted.

Many houseplants like being potbound. English ivy (Hedera helix), pothos (Epipremnum aureum), Philodendron, palm trees, Ficus trees, African violets, succulents, snake plants (formerly Sansevieria, now Dracaena), and bonsai prefer somewhat cramped quarters. Many potted herbs (rosemary, lavender, chives, sage, thyme) also fare better when potbound. But, in order to ensure good health, gardeners must provide nutrients according to the needs of the particular plant, and according to the time of year.

It’s helpful to know the habits and preferences for each kind of plant. For example, although the 4′ tall variegated snake plant (Dracaena trifasciata ‘Laurentii’) eventually will need a 10″ or 12″ pot, its cousin, the dwarf bird’s nest species (D. hahnii), can stay in a 4″ or 5″ pot for many years!

Fertilizing Houseplants

Most tropical plants spending the winter indoors won’t need fertilizer until late winter or early spring. If they continue to grow and look healthy, and they’re receiving good light, though, diluted solutions (1/4 to 1/2 strength) can be added every 4 to 6 weeks. Err on the side of using less fertilizer in winter.

As long as they’re properly watered and fertilized, your plants can remain perfectly happy while potbound. In fact, they’re easier to manage this way, since there’s less likelihood of overwatering. But you’ll have to water more frequently.

Look for products formulated for foliage houseplants or for flowering plants. They’re available in several forms: timed-release prills (use a low dose from fall through winter), liquids, granules, and soluble crystals. Read the label.

Fungus Gnats

Plants in smaller pots are less susceptible to diseases, root rot from overwatering, and fungus gnats. Ever have those annoying little “fruit flies” around your houseplants? The simplest remedy is to allow the soil surface to dry out.

Female fungus gnats lay eggs on moist soil. When the tiny larval worms emerge, they eat small roots, sap on cuttings, fungus, and organic matter in the top inch or two of the soil. Let the surface of the soil dry before watering again, and you’ll have fewer fungus gnats. See if adding a 1/2-1″ layer of pine fines as a mulch might prevent gnats from laying eggs.

Yellow sticky cards are good for catching flying insects. A card placed horizontally near the plants, on the pot’s rim, or in a sunny window attracts the most gnats.

Save the Spider!

A green spider plant.

The spider plant in the 4″ pot that your girlfriend gave you two months ago is literally crawling out of the pot. She propagated it from one of her own plants, so it has sentimental value.

Spider plants, related to other strong-rooted Asparagaceae (formerly Liliaceae) family members, develop roots that circle around the inside of the pot. The vigorously growing roots raise the entire plant higher in the pot, opening up air spaces around the root ball. This dries out the finer roots, and water gushes immediately through the drainage holes without moistening the soil. Clearly, it’s time to work on this one.

When Should I Transplant Houseplants?

A good time to transplant houseplants is in spring to mid- or late summer. Plants that recover slowly (for example, succulents) should be repotted, if needed, by mid-summer. In autumn and winter, plants receive fewer hours of daylight, photosynthesizing at a reduced level. Our slower growing tropicals don’t grow much foliage in autumn and in winter. And roots also are reluctant to grow.

Cooler temperatures, compared to the balmy summer days spent on the porch, cause systems to slow down. So, trying to force plants to grow at a time when they’re entering semi-dormancy often does more harm than good. Plopping a plant’s almost dormant root system into wet soil and expecting it to grow is asking the plant to do something against its nature. It would rather stay semi-dormant.

Providing a greenhouse atmosphere—warm, humid, and sunny—keeps your houseplants in much better condition, even through the shortest days of winter. Optimal light levels increase rates of photosynthesis, respiration, and transpiration. As a result, they might grow almost as fast as they did in June.

Providing a greenhouse atmosphere—warm, humid, and sunny—keeps your houseplants in much better condition, even through the shortest days of winter. Optimal light levels increase rates of photosynthesis, respiration, and transpiration. As a result, they might grow almost as fast as they did in June.

But most of us deal with dryer air, energy-saving chilly nights, and dim lighting (in the plants’ eyes) until the hyacinths bloom outside.

Plants, both indoors and out, take on renewed vigor once the days lengthen closer to springtime. Some of us humans do, too.

How Big Should the Pots Be?

Succulent dish garden in ceramic bonsai tray.

I’ve grown dwarf peperomias and miniature succulents, such as Echeveria minima and Haworthia truncata, in 2″ pots for many years. Since the succulents are prone to rot in wet soil, keeping them very potbound decreases the chances. There simply isn’t that much soil in the little clay pot, and it dries fast in direct sunlight.

Most of the succulents I enjoy growing are on the small side, anyway. Almost all are in 1½” to 4″ pots, and others have been planted in larger, but shallow, bonsai trays (photo, right).

I brought with me from Maryland a 4½” pot of Drimiopsis kirkii, one of the leopard lilies, and it has yet to be repotted into a larger pot, 6 years later. Its cousin, Drimiopsis maculata, however, grows from bulbs which multiply faster than those of D. kirkii. So D. maculata gets divided more often, but they’re still in 4½” pots.

Dracaena hahnii, the dwarf snake plant, lived happily for years in a 4½” pot. The small, glossy-leaved Spathiphyllum wallissii would have complained if it had been bumped up into anything larger than its 6½” plastic pot.

A pink flowering miniature cyclamen stays in its 4½” pot (photo, above), year after year. It is now coming out of dormancy and beginning to grow new foliage, contrary to what most other plants are doing. That’s because its growth cycle calls for cool to cold, but not freezing, temperatures in order to set flower buds. It will be fertilized accordingly, for a full canopy of marbled leaves.

The plant’s habit and its root structure help determine the required pot size. In general, transplant houseplants into pots that are only 1″ to 2″ wider, and only if they need it.

The Old Weeping Fig

Variegated weeping fig.

A weeping fig (Ficus benjamina), given time, will grow to the ceiling. Instead of raising the roof, its height can be managed by “aesthetically” cutting stems back in the spring, when it will respond faster.

I grew a variegated weeping fig in a 14″ pot for about 15 years, in front of a big window that received a few hours of morning sun. When the tree grew to almost 8′ tall, above the top of the window, I pruned it back a few feet. Then, when it regrew, all the foliage was once again in the sun and at eye level.

African Violets

A healthy African violet.

African violets (Saintpaulia ionantha) are happy to stay in 4″ pots for years. Miniature African violets need smaller pots than that.

A rule of thumb for pot size and an African violet is to plant it in a pot that is 1/3 the spread of the foliage. So, a 4″ pot will accommodate a plant that is 12″ wide. Plants in top condition might take a slightly larger pot, but you have to pay very close attention to moisture and soil drainage.

“What should I do with an African violet that has a long trunk?”

As these plants grow new leaves from the top of the rosette, older leaves lower on the stem die off. That’s part of their natural growth pattern. When the plant develops a trunk, it’s time to make an adjustment. But don’t do this if the plant is slowing its growth. Spring to mid-summer is a better time for this procedure.

Remove the plant from its pot and slice off the bottom third of the root ball. Shave off a small amount from the sides as well. Wash the pot, check the plant for insects (mealybugs, especially), and treat with horticultural oil if necessary.

Place a small amount of African violet potting soil in the bottom of the pot. These plants like peat moss in their mix. Set the plant in the pot, and fill in the sides with more soil, using a chop stick to firm soil in the gap.

Part of the trunk will now be loosely covered with soil, and it will grow new roots. The top of the root ball should be lower in the pot than it grew previously. (Yes, this is exactly what we don’t ordinarily recommend.) Water it in, using lukewarm (about 85°F) water. Keeping the soil too wet will rot the trunk and the roots.

Use the kitchen sink sprayer to wash soil off the leaves, using lukewarm water. Towel off the water drops, and let the plant dry in a warm location.

It’s less stressful for these plants if this is done every year or two, before the trunk grows a few inches tall. But I have seen perfectly happy violets with long stems curling over the edge of their pots.

“What are those marks on the leaves?”

Water the soil—always lukewarm for African violets—and avoid wetting the leaves. If water splashes on the leaves, absorb it with a towel, and let the plant dry in a warm place. As drops of water chill on this plant’s leaves, unsightly tan or brown rings and lines will be left behind.

Grow African violets at 70 to 74°, and fertilize regularly with a product formulated for this genus.

Less Is More

Move miniature species of plants into something only 1/2″ to 1″ larger, if they need it. I know; that doesn’t seem like it could make much of a difference. But for the plant whose roots, in the wild, might be crammed between layers of sedimentary rock on a blustery cliff, 1/2″ is plenty.

Move miniature species of plants into something only 1/2″ to 1″ larger, if they need it. I know; that doesn’t seem like it could make much of a difference. But for the plant whose roots, in the wild, might be crammed between layers of sedimentary rock on a blustery cliff, 1/2″ is plenty.

Large-growing plants require new pots up to 2″ wider in diameter. Peace lily (robust varieties of Spathiphyllum), weeping fig (Ficus benjamina), Chinese evergreen (Aglaonema spp.), and larger palm species can be moved from 6″ starter pots into 8″ pots. And, importantly, this assumes that the roots tightly fill the smaller pot.

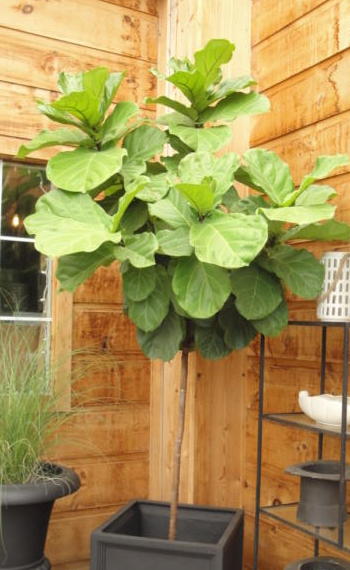

Many of the tropicals will survive and prosper over the next several months, even while very potbound. If they’re already in 8″ pots, they’ll likely be fine until spring, when they can be potted on if needed. The 6′ tall fiddle-leaf fig in an 8″ nursery pot, though, can go into a 10″ pot, since the heated sunroom has floor-to-ceiling windows. Sunny conditions encourage plants to grow new roots, but carefully monitor soil moisture. Avoid watering houseplants (especially succulents) on cloudy days.

If growing conditions in your home are not ideal, but plants absolutely need to be repotted, transplant them now, before fall, into slightly larger pots. Wait until spring to transplant large houseplants, if it’s needed at all.

Houseplants don’t require repotting every year. Once they have attained a mature size, they no longer need to be moved into progressively larger pots. Instead, regularly fertilizing with products formulated for houseplants will supply all the nutrients they need.

Headings:

Page 1: Should We Transplant Houseplants Now?, Inspect Them First, Do Your Plants Actually Need Bigger Pots? (Fertilizing Houseplants, Fungus Gnats, Save the Spider!), When Should I Transplant Houseplants?, How Big Should the Pots Be? (The Old Weeping Fig, African Violets, Less Is More)

Page 2: Prepare for Transplant (Root Insects, Speaking of Spider Plants, Roots-Air-Water-Light) and Potting Up (Score the Root Ball, Potting Soil, Begin Filling the Pot, Downsizing, Water It In)