Brassicas germinated 3 days after sowing seeds in these round 6″ pots.

Sowing Seeds For The First Crops: Too Early?

The calendar is approaching my favorite part of the year—warming temperatures… birds singing their special songs… starting seeds for the garden. New crops of brassicas—arugula, broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, collards, kale, mustard greens, pac choi—top the list. I also grow lettuce, spinach, Swiss chard, peas, bunching onions, and others. In this article, I’ll describe an easy step-by-step process for sowing seeds you can do right now.

Bumble bee on ‘Arcadia’ broccoli in spring.

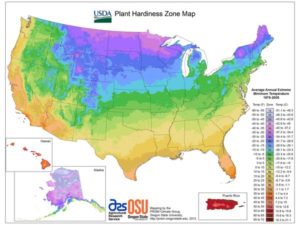

Some varieties of leafy greens are productive from early autumn through spring here in zone 7b, in the Piedmont of North Carolina. Last fall’s crops will flower in late winter or spring (photo, right), and are then replaced with young transplants. With cooperative weather, cool season crops offer a fantastic return on investment!

Starting in early March, I’ll sell transplants at local farmers’ markets or plant them into my own gardens. In preparation for the season, though, growers have nurtured these plants for 4-6 weeks before they’re offered for sale.

It’s important to plant young plants; heading crops, such as broccoli and cauliflower, confined in cell packs only 1 or 2 weeks too long will not properly head up. So, it’s important to start sowing seeds at the proper time—not too early and not too late.

Gardeners living in colder climates need to adjust their gardening calendar accordingly. Yes, at this time, it might be too early for some. Leafy greens prefer chilly weather. Many fail in the heat of high summer, although they might succeed in northern gardens (northern hemisphere) at that time. With careful variety selection and placement (light shade during the hottest hours of the day), we can stretch the season for these healthy greens.

“How do I use these greens?”

Although I’m not a vegetarian, cool season greens are the foundation of my diet. I can’t tell you how satisfying it is to pick fresh greens for salads, sauces, veggie omelets, soups, sandwiches, and stir-fries in winter. And as a side dish, on pizza, with pasta, and in smoothies, if you like them. It never gets old!

Cool season greens are versatile in the kitchen but curiously underrepresented in our gardens. Considering the fact that many contain the highest levels of vitamins, minerals, fiber, and beneficial antioxidants among edible foods, it’s a wonder more gardeners aren’t growing them! The brassicas (Brassicaceae family, formerly Cruciferae) are particularly nutrient-dense, and this family of plants is the only one with measurable amounts of the sulforaphanes. Sulforaphanes are antioxidants that help prevent cancer, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and inflammatory illnesses. They also help maintain eyesight, brain function, and heathy skin.

Growing your own produce from seed saves money in these times of high inflation. You can harvest what you need for the day, so nothing goes to waste. And most crops can be grown cleanly, without pesticides, before the insects move in. Furthermore, there are hundreds of varieties to choose from that never appear in garden centers or grocery stores.

Maybe you’d enjoy experimenting with new varieties each year, as I do. Some have become my favorite foods, so they’re planted in my gardens each year. Among cool season greens, those include my favorite vegetable—mini broccoli ‘Happy Rich’—as well as ‘Nabechan’ bunching onions, Johnny’s AllStar Gourmet Lettuce mix, a butterhead lettuce called ‘Skyphos’, arugula ‘Astro’, ‘Arcadia’ broccoli (in autumn), dinosaur kale, and ‘Sugar Snap’ and ‘Oregon Giant’ peas.

Ready to begin?

Preparing To Sow Seeds

Pepper seeds sown in a 9-cell market pack.

It’s helpful to read this entire article before proceeding so you can gather materials and plan your setup. You will need:

- supplies (cell packs or pots, flats, labels, soil, seeds, vegetable fertilizer)

- warmth to start the seeds

- a waterproof surface

- adequate light to keep seedlings healthy and strong

- timely transplanting to prevent crowded plants

- detailed records for future reference

Perhaps you’ve chosen lettuce, arugula, and ‘Black Magic’ kale seeds for your first project. You’ll need clean cell packs or pots, fresh seedling mix, and at least one flat to keep them in. You might already have used pots and flats lying around somewhere. Clean them first with a 10% bleach solution to kill pathogens.

Instead of trashing the failing window blinds, I cut the plastic slats, which make perfect plant labels. You can also use a plastic milk jug. Sharpie pens write smoothly, but the ink eventually fades in bright sun. Placing the label below ground or on the shady side of the plant keeps it legible for a while longer. A journal or a computer log is recommended as a backup and for additional notes.

I recently bought a few inexpensive heavy gauge flats from a big box store. Made by Ferry-Morse, they have no holes in the bottom and measure 10 x 20½” (inside diameter). They’ve proven their usefulness for holding pots of germinating seeds, so I’ll go back for several more.

Temperature For Sowing Seeds

Successful germination depends on a source of warmth if your home is on the cool side, as mine is. Although lettuce can sprout at 40-50° F, it germinates erratically or not at all above 70-75°. Other greens will get off to a better start when the soil temperature is in the 70’s to low 80’s. After germination, these seedlings will need cooler temperatures.

What are the options? Heat mats are available. One that measures 21 x 21″ consumes 45 watts of electricity and costs about $40-60. Larger commercial sizes, for 8-10 flats, cost over $125.

Maybe the top of the water heater provides suitable temperatures for starting a few pots of seeds. You might need to moderate the heat by raising the pots above the warm surface. Check them daily!

Miniature Incandescent Christmas Lights

These brassica seeds germinated overnight, above the mini lights.

I use indoor/outdoor miniature incandescent Christmas lights for warmth—not light—under the seeded flats. One 100-bulb string of lights (approximately 40 watts) on the hard floor of the spare bedroom and covered with 6 upside-down mesh flats (photo, above) works for me. Their gentle warmth is distributed over a large area, so I can start many flats of seeded pots at one time.

Be careful not to crush any bulbs, as this can cause remaining bulbs to burn hotter or to go out entirely. Don’t use higher wattage bulbs. Safety first!

You might want to test this layout before proceeding. Perhaps you have a folding table or counter space in the utility room that could serve this purpose.

When that greenhouse kit gets built, I’ll probably start seeds out there. Indoor space is very limited, and plants fill every bright window. Now that the knee replacement has improved mobility, I’ll work on a more efficient infrastructure for sowing seeds and transitioning them to outdoor growing. Maybe I’ll start seeds indoors and grow them on in the minimally heated greenhouse; it all depends on the severity of the weather and electric rates.

Preparing Pots For Sowing Seeds

A flat of seeds over mini lights, with plastic to hold the warmth until seeds germinate.

I start over 200 varieties of plants for the farmers’ markets, so many of the flats are shifted around almost daily. After the first round of seedlings has been transplanted, I start another. Some varieties need more time to sprout, while others, such as arugula, germinate in just 2 days.

A sheet of clear plastic over the flats holds in humidity and warmth from the mini lights. Labels identifying each variety hold the plastic above the soil. For good air circulation and to let condensation evaporate, keep the plastic open on the edges.

Light For Germinating Seeds

Your seedlings must receive direct sunlight or strong artificial light as soon as they emerge from the soil. One or two days in inadequate light will cause the seedlings to weaken and stretch toward the light, so don’t delay getting them into the sun.

From horticultural supply companies, you can find ready-to-assemble light stands with shelves and LED fixtures. There’s one with 3 shelves, six 4′ LED tubes, and an attractive powder-coated aluminum frame that costs $1,000. Smaller units for 1-3 flats are more affordable at $100-400. They might give off enough warmth to satisfy the need for warm soil. One advantage in using this setup is that the light fixture above each shelf sustains transplanted seedlings for 2-3 weeks as long as the temperature is at acceptable levels. Cool season greens do best with a drop in temperature (below 60-65°) after germination.

You won’t need advanced carpentry skills to put something together yourself. One or two 4′ long shop lights each fitted with 2 daylight (full spectrum) tubes (LED or fluorescent) cost $30-70. Use 2 x 4’s for the supporting framework or suspend the fixture under a table. Chains and S-hooks raise or lower the fixture, or simply elevate the seed trays to get them closer to the light.

In My Basement

In the basement and over two 6′ tables, I nailed chains and rope to the floor joists and positioned the lights as needed (photo, above). I’ve used these fixtures for decades to start seeds and root cuttings, to rehabilitate plants, and to grow delicate species and stock plants.

Plants that need strong light (vegetables, herbs, succulents) grow only 3-4″ below the tubes; 12″ below the tubes, however, is too far away. Light intensity drops precipitously with each inch of distance from the light source. Running the fixtures for 16-18 hours per day should supply enough energy for the plants to grow normally.

Seedlings won’t mind 24/7 lighting over the short term. Not turning the lights on and off every day adds to their longevity.

I prefer to start seeds without relying on electricity, using just the sun. But, at times, starting seeds under these light fixtures is convenient, particularly when they can grow there for a week or two before I’m able to transplant them.

Natural Sunlight And Temperature

Seedlings and fresh transplants enjoy the protected space on the porch.

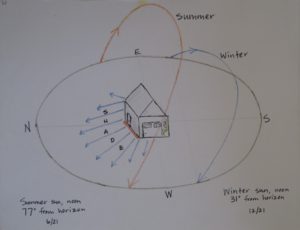

Newly transplanted seedlings go out to the sunny enclosed porch (photo, above), which faces south. I usually keep them there, in bright but filtered sun, for their first 1-2 days. On an overcast, calm day, new transplants can go outside if the temperature is above 50°. When the wind’s blowing, though, I keep the flats on the porch and vent the plastic to admit cool air. The enclosed porch—when the plastic “door” is closed—heats up to 90° or higher on a sunny winter day.

For a few nights when the porch was too cold for young plants, I brought them back indoors. Now, at the end of February, dozens of flats stay outside on woven ground cover (a durable polypropylene fabric), hugging the wall of the porch. That’s on the south side of my house, a warm microclimate. There’s less wind here and nighttime temperatures rise a few degrees above areas farther from the house.

Success depends on temperature, so I check expected hourly temperatures daily and the forecast for the coming week. I cover the flats with plastic or an old sheet when they need a little protection. But, at this stage, they’re becoming more resilient to temperature fluctuations.

In the morning, I’ll remove the plastic and let them bask in the sunshine. Those little seedlings double in size in a week, and roots are filling the pots. Almost ready for the market!

How Low Can They Go?

Maturing seedlings of cool season greens tolerate temperatures in the high 20’s and 30’s. They’ll take temperatures lower than that when they’re a bit older and planted in the garden. Remember, this regimen applies to cool season greens and vegetables, not to main (summer) season crops, which need a frost-free environment.

In this part of northern North Carolina, elevation 1200′, late February temperatures range from the mid- to high 50’s in the daytime to the mid-30’s at night. Keep in mind that those are averages and that actual temperatures can vary considerably from the average.

As an experiment, I left 3 containers of newly transplanted ‘Freckles’ lettuce seedlings outside, exposed to 21-22° on 2 nights. They’re fine! Lettuce resists damage better than some of the other crops.

One Step At A Time

We don’t want to subject tender seedlings only a few days old to the rigors of outdoor conditions, especially freezes and wind. Indoor-grown seedlings that received less than adequate sunlight will need a more gradual transition. Some will thrive, while others—the spindly, weak ones—will sulk or die.

When in doubt, proceed in incremental steps—gradually lowering the temperature and introducing seedlings to increasing sun and wind speeds. (For summer vegetables, harsh sunlight is another factor to consider.) This is called hardening off. Assuming the weather cooperates, vegetable plants can be hardened off within one week.

Root systems grow quite fast in order to supply water to foliage and stems. Leaves adapt to prevailing outdoor conditions, growing a thicker cuticle. The cuticle is a protective waxy outer layer over the epidermis, designed to slow moisture loss from within the leaves.

Growing On To Transplant Size

Broccoli, turnip greens, cabbage, and arugula seedlings hardening off next to the porch.

Choose a location where your plants can grow for another 2-3 weeks before they’re planted out. Maybe that’s a sheltered patio or the sunny side of a carport. You might need to take them indoors for the night if it’s too cold.

Check local weather reports, paying close attention to nighttime temperatures. If the cool season greens have been properly hardened off, they shouldn’t be damaged by temperatures around 30°F. After the first week, they’ll tolerate temperatures down to the mid-20’s, and some even lower.

Research the varieties you’re growing. A few cool season vegetables, such as ‘Tokyo Bekana’ Chinese cabbage, tatsoi, and Swiss chard exposed to extended periods of cold weather might bolt (flower prematurely) before reaching full size. Have an old sheet or floating row fabric available to cover them on cold nights. I’d rather plant these crops and take a chance with the weather than let them get potbound in their cell packs.

Soil warmed by the sun lends some protection to plants in the ground. Or you could repot them into 1-2″ larger containers and protect them indoors at night if it’s still too cold.

Alternatively, a caterpillar tunnel or similar clear covering placed over the garden row can protect transplants during a stretch of freezing weather. Vent it in the daytime to prevent overheating. A cold frame helps plants transition to outdoor conditions.

Good planning includes preparing garden soil so it will be ready to receive your transplants when that moment arrives.

Agricultural extension offices print spreadsheets online that indicate when to plant seeds or transplants into the garden. This guideline for sowing seeds helps keep North Carolina gardeners on track, although we need to heed local weather forecasts.

Fertilizer

Lack of fertilizer in ‘Freckles’ lettuce compared to 2 pots that were fertilized.

Potting soil normally doesn’t remain fertile for more than 2 or 3 weeks unless timed-release fertilizer is included in the mix. The package’s ingredients label should indicate whether or not fertilizer has been added. To maintain steady growth of seedlings, fertilize with a product formulated for greens or vegetables every 2 weeks starting 2-3 weeks after germination.

Rain and frequent irrigation rapidly leach the primary nutrient needed for greens—nitrogen—through the soil. Running low in nitrogen stresses plants, and they might not recover when they’re planted. Always keep these seedlings evenly moist—but not wet—to prevent checking their growth. Heavy rain necessitates more frequent fertilization (photo, above).

From speaking with my customers over the years, it appears that many are hesitant to use any kind of fertilizer on edible plants. Fertilizer is not toxic! Organic sources and chemical (or synthetic) sources of fertilizer break down to the same molecules, and the plant, to a large degree, decides which ones to absorb. Organics add other beneficial nutrients to the soil.

In cold soil, microbes that break down fertilizer into usable forms are not active. So, using a synthetic fertilizer in winter supplies the needed nutrients until the ground warms up. Otherwise, I do prefer organic fertilizers in all my gardens. Used frequently, chemical fertilizer kills microbes and earthworms living in the soil.

Continued on Page 2.

Headings:

Page 1: Sowing Seeds For The First Crops: Too Early? (“How do I use these greens?”), Preparing To Sow Seeds (Temperature For Sowing Seeds, Miniature Incandescent Christmas Lights, Preparing Pots For Sowing Seeds, Light For Germinating Seeds, In My Basement, Natural Sunlight And Temperature, How Low Can They Go?, One Step At A Time), Growing On To Transplant Size (Fertilizer)

Page 2: Sowing Seeds: The Process, Transplanting Into Larger Containers (The Process, Sowing Seeds and Transplanting In Multiples)

…Yes we can! Growing basil in pots is the answer! Take the pots indoors in rainy weather to prevent spores from germinating.

…Yes we can! Growing basil in pots is the answer! Take the pots indoors in rainy weather to prevent spores from germinating.